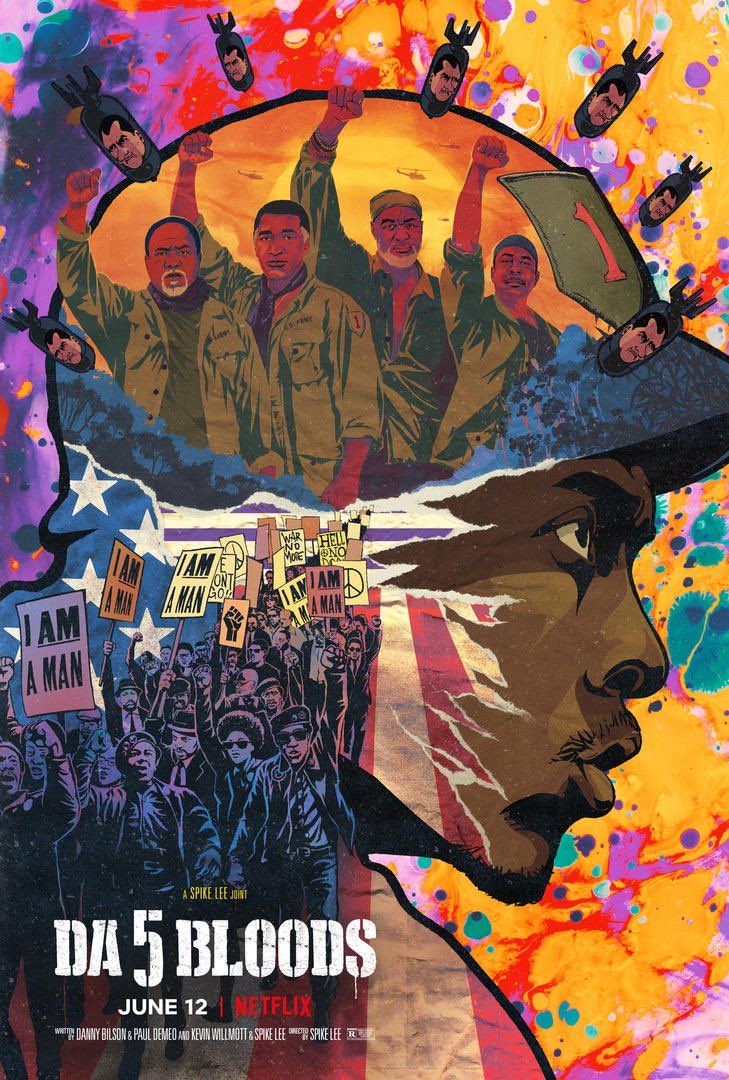

'Da 5 Bloods' review

Is Spike Lee influenced by the pioneers of African cinema? As his 21st joint, the buoyant, pulsating yet tragic 'Da 5 Bloods', overwhelmed me, the tip of Lee’s incisive creative and didactic spear here, the excellent Delroy Lindo’s Paul seemed to be in conversation with one of the more devastating characters from Ousmane Sembene’s catalogue; Pays from 'Camp De Thiaroye'.

Is Spike Lee influenced by the pioneers of African cinema? As his 21st joint, the buoyant, pulsating yet tragic 'Da 5 Bloods', overwhelmed me, the tip of Lee’s incisive creative and didactic spear here, the excellent Delroy Lindo’s Paul seemed to be in conversation with one of the more devastating characters from Ousmane Sembene’s catalogue; Pays from 'Camp De Thiaroye'.

Someway down the film, there’s this shot of Paul, a Vietnam war vet giving the black power salute after an intense three-minute rant, the kind we've seen Lee deploy before. Up there with the most essential conceptions in Black Cinema, Paul is teeming with pain, resilience and holy conviction. But he’s also wearing a MAGA hat, as crimson as sin in need of cleansing.

In 'Camp De Thiaroye', Pays is a mute PTSD-ridden Senegalese soldier returning from the frontline in WWII after fighting under the banner of his French oppressors and serving time in a POW camp. Most of the time we see him, he has on an SS helmet which shrieks at us with its cursed iconography.

I have described Pays as a repressed prophet without a voice but he, like Paul, is a meditation on the complex postwar identity of an oppressed class. These strained identities are painfully spawned from a context that had them fighting for their oppressors as, in the case of Senegal, French soldiers massacred women and children back home, whilst in the US, there has been a perpetual chain of state-sponsored violence against black bodies for centuries. The SS helmet and the MAGA hat Pays and Paul don are but scars; scars that run deep through the film right into our hearts.

The first words we hear in 'Da 5 Bloods' are from Muhammad Ali’s inspired explanation of why he refused to enlist in the Vietnam War. Lee’s opposition to the war is crystal and his solidarity with the Vietnamese people a gyre of warmth. The way he deploys the Vietnamese flag kind of springs up on you in the way the star-spangled banner beams with pride in ‘25th Hour’. The only pride on show here is for his fellow black man. Black lives have always mattered to Lee and his message has remained eerily relevant to the global discourse across four decades.

'Da 5 Bloods' has a lot on its mind and I guess it is a bit of knock on the film that its ideas perhaps were deserving of more narrative and tonal dexterity. In a plot that brought back fond memories of a childhood favorite of mine, the Gene Hackman-led ‘Uncommon Valor’, 'Da 5 Bloods' has the workings of a fun heist adventure that sees four black veterans who return to Vietnam to recover the remains of their slain unit leader from the war and search for a buried cached of gold they hid decades earlier.

For the aging quartet, we meet the “Pigeon-toed” Eddie (Norm Lewis), a seemingly successful businessman; the cheerful and surprisingly fit-looking Isiah Whitlock Jr as Melvin; former medic and brains of the operation Otis (Clarke Peters) and then there’s the feisty Paul (Lindo). They are being helped by a fixer, Vinh (Johnny Tri Nguyen), one of the more prominent Vietnamese characters.

Also flying the Vietnamese flag is Tien (Le Y Lan), a former sex worker Otis was intimate during the war. She hooks them up with a French businessman (Jean Reno) who is ready to help them change the gold into a medium easier to carry out of Vietnam. He demands a 20 percent cut. Paul is not happy with the arrangement and is on the constant lookout for the first sign of heat.

The Bloods encounter a few other relevant faces on their adventure; Hedy Bouvier (Mélanie Thierry), a bleeding bundle of white guilt who has dedicated her riches to dismantling mines from the war alongside Simon (Paul Walter Hauser) and Seppo (Jasper Pääkkönen).

The fifth member of the blood varies depending on the timeline we are in. In the present day, Paul’s son, David (Jonathan Majors) worms his way onto the treasure hunt via a silly plot point. But with some quaint edits, reversions to 16 mm newsy film stock and more squarish aspect ration, we flashback to the Vietnam War (where all four older actors still play themselves without any de-ageing) to spend time with their squad leader, Norman (Chadwick Boseman), who assumes hallowed status as the film progresses.

Like ‘Apocalypse Now’, which Lee pays homage to multiple times here, the journey is a descent into the madness that is the heart of America. It starts out with our four guys getting their groove on in a club. What follows is a treacherous journey filled with internal and external dangers as we sail upstream; minefields, scheming Frenchmen, still-angry Vietnamese as well as the greed and paranoia that stem from fraught bonds and guilt.

Some other film references come in the form of critiques or just plain mocking. It stung a little when Fugazi and Rambo movies were used in the same sentence by Melvin. Then again 'First Blood' technically isn’t a Rambo film. Some shade is also thrown the way of Chuck Norris and the ‘Missing in Action’ b-movies. “All those holly-weird motherfuckers trying to go back and win the Vietnam War.”

Lee then follows up the criticism of the whitewashing of the Vietnam War history with education, cutting in pictures of the likes of Milton Olive, the first black man to win a medal of honor, as the film trots on. Our director does similar things with stills from the harrowing My Lai Massacre, Martin Luther King Jnr’s assassination among others.

It’s the kind of overtness I have become increasingly comfortable with because of how it mimics the directness and urgency of classic African cinema. When you approach every film like it may be your last, you do not hold back on your messages of enlightenment.

Enlightenment is what we get a lot of from Norman in the flashbacks. He is compared to a religious figure at some point and their journey to retrieve his remains has the makings of a pilgrimage. Boseman exudes a calm but radiant charisma in the way he embodies Norman, whose moniker prefix, “Stormin”, feels like an oxymoron.

He speaks truth to power and streams of wisdom flow down from him as well as awareness of the unappreciated sacrifice of black men in the war. It’s why when they Bloods first find the gold on a crashed CIA plane as part of a mission, Norman decides to view it as reparations; some thin facsimile of justice.

Norman also represents torment to Paul, who still calls out his name in his sleep. He was the only one of the four who saw him die. He initially feels most committed to finding Norman’s remains than the gold. But the more we spend time with Paul, the more we realise his canvas is the centrepiece of the film; offering layers and texture that Lee executes masterfully.

On the lighter side, Paul is a troll job in the vein of ‘Chiraq’s pantomime war general clad in confederate flag underwear or the screening of ‘Birth of a Nation’ in ‘Blackkklanman’. He spews ignorant anti-immigrant propaganda, is still bigoted towards Vietnamese people and proudly claims he voted from “President Fake Bone Spurs.” And I probably shouldn’t have been howling here but there's a point when an angry Vietnamese man brings up the My Lai massacre to Paul and he dismissively retorts: “there were atrocities on both sides.”

Lee digs deeper into Paul though, revealing his troubled and sometimes outright toxic relationship with his son by way of moments of glorious catharsis and cruel dissonance. Lindo has already been hailed as a powerhouse in this film but I suspect it will take more viewings to appreciate the subtlety exuding from Majors, who like the rest of the cast, is not a hair off the wavelength Lee requires of them.

There’s nothing subtle about Lindo though. I do not want to disrespect Denzel Washington’s turn as Malcolm X under Lee’s auspices but Lindo is in God mode here; delivering the first truly electrifying performance of 2020.

As I said, Lindo is the tip of the spear for Lee and his ability to harness the most primal of emotions left me in awe. There isn’t the linear descent into psychological bedlam one would expect upon seeing the iconography from ‘Apocalypse Now’. There are instead contained and measured explosions from Paul that push us towards the film’s central truths.

There are times Paul is a manifestation of America’s history of violence, sometimes mistaken as badassery. He also morphs into the dark side of the warning given him by Norman; about war being money and money being war. Think dragon sickness from Tolkien lore. But most poignantly he is a wounded and angry black man broken by his country.

Much will be made of the aforementioned rant against the US government and us; where he becomes Lee’s own voice in the desert crying. But the scene in 'Da 5 Bloods' that broke me evoked the final moments we spend with Ben Foster’s PTSD-stricken character in Debra Granick’s ‘Leave No Trace’ as Paul howls and lumbers like a wounded bear towards a forest as he cries out Psalm 23 like a man on the gallows. I felt the cold grasp of damnation reaching towards me.

Like the Vietnam war itself, noble intentions only took one so far. The Bloods were ultimately returning to cursed ground and the desire to rally for their dead leader battles against the weight of an unjust war amplified by their standing as black Americans. As the story develops, you realise there is a timelessness to the toll of the war on this fraternal unit and a purpose to keeping their ages consistent across timelines five decades apart. It’s not that they carried the trauma of Nam away with them. They never really left.

And the trauma of being black in America still filtered through to the soldiers in the war. In a flashback, the Bloods listen to Vietnamese DJ, Hanoi Hannah, who announces the death of Martin Luther King Jnr to the Black GIs. Four of the Bloods are ready to raise hell, much like many black people today angered by the police murder of black men. But Norman, in the moment, rises from his Huey Newton-esque throne of palm branches in messianic splendor and calms them down.

The detail and flourishes are markers of an auteur at the top of his game. Lee’s meshing of style and idealism in mainstream American filmmaking is probably only matched by peak Oliver Stone, a filmmaker who did well not to whitewash his own account of the Vietnam War. Stone’s influences may even run deeper when you consider the way Lee is becoming more and more comfortable with weaving archival footage into his films. Also, if you squint a little it feels like Lindo is channelling the essence of Willem Dafoe and Tom Berenger from ‘Platoon’.

Lee is, of course, doing much more than lament about the horrors of a misguided war. Otherwise, this would just be ‘Triple Frontier’. He’s as always all about centring the black experience and giving it life and humanity. He does so in a film that is entertaining as hell, violent and an incendiary, even if sometimes unbalanced, mix of tone and genre carried on the visceral presence of Marvin Gaye, whose work on the soundtrack is almost as important as Lindo at the centre of the film. And the two combine for a haunting rendition of a song called ‘God is Love’. A moment of real power.

I end with the question I started with: Just how much is Lee influenced by the pioneers of African Cinema? There doesn’t appear to be much of a link given his past declarations. He has always considered the “Treasure of the Sierra Madre” to be one of his favourite films and that is noted as one his influences in ‘Da 5 Bloods’.

No African filmmakers feature on Lee’s list of essential films for young filmmakers. But would that list change if it was a list for young black filmmakers? Maybe. The art of black filmmakers gushes forth from a collective trauma that has defined our realities tailored the calling of many artists. Lee is drawing from the same well of black tears as the Sembene, Sissako and other icons for African Cinema. Like these icons, Lee makes his politically charged art in hope of a day when the well will run dry.